Tuesday 6th of February, 2024.

Written by General Psychologist, James Blaze.

New year, same problems: How to take on the problems that have been holding you back

Are our problems the problem, or our problem-solving ability?

From financial restraints, social relationships, academic challenges, health concerns, romantic issues, familial tensions and career-based setbacks, life often involves problems that can get in the way of our goals and overall happiness. If not handled effectively, not only will these problems remain unresolved, but we could experience negative effects on our mental health.

At the beginning of the new year, it may be a good time to ask ourselves if we are still sitting with unresolved problems from the past or whether we anticipate new ones? Better yet, we could ask ourselves if we are good problem solvers and if not are we ready to change this?

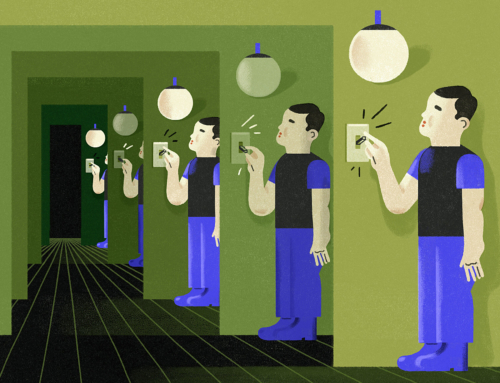

People generally tend to fit into three kinds of problem solvers based on how they perceive and react to the issue at hand. Firstly, there are those who see the issue as a challenge instead of a setback. These people often believe the problem does have a solution and requires time and effort to plan and execute. With such beliefs, these kinds of people often address the issue head on after careful deliberation. There are also many of us who perceive the problem as a threat to wellbeing, focusing on its capacity to shake up our lives and the catastrophic aftermath that could follow. Those of us like this often view the problem as unsolvable or if not, too hard to solve on their own, opting to delay action or tolerate the consequences of it remaining unaddressed. Finally, there tends to be people who see the issue as solvable but fail to exercise the proper planning necessary to successfully reach the desired outcome, instead opting to rush to any solution they think might work.

Think about how you have generally been inclined to solve problems in the past and which problem solver you think are; the positive systematic type, the negative avoidant type or the impulsive type. On reflection of your past problems and how you handled them, which was greater, the problem or how you handled it?

Solving our problems, not just for now but for the long term.

The diversity and severity of problems can be so varied at different parts of our lives that at one point or another we are bound to have had or have trouble making decisions. Learning the skill of how to make logical, systematically informed decisions and implementing them might go a long way beyond the issues we have right now. Here is a guide to helpful decision making:

- Define the problem. First, we want to define what the problem is that is troubling us. Don’t be vague. Instead of identifying “my marriage is not in a good place”, be specific and detail, “my partner and I are not communicating like we used to”. Breaking the overall issue into a smaller problem can be helpful to focus on what the issue actually is.

- Brainstorm list of possible solutions. Be sure to list all the possible solutions, even if we think they are not so feasible. This helps develop self-efficacy that we can in fact, be resourceful to ourselves. In making an extensive list of possible solutions, it can be helpful to remember ways we tried to solve similar problems in the past, even in a different context. We may be able to draw out important lessons that worked.

- Evaluating and deciding. Here is where the careful planning and consideration takes place. Explore and tally the positives and negatives that come from each possible solution, reaching a net tally in favour of positives or negatives. It might be of use to rank the top three or five most appealing solutions based on how long your list is. Having alternatives may be helpful if our selected solution does not go our way. Once we have selected our best solution, we can try visualizing implementing it going our way or imagining what the outcome feels like when we complete it. This spur us on to keep going when the chosen solution is scary.

- Implement the solution. Finally, we are at the stage of putting our chosen solution into practice. If we are feeling uncomfortable about this, try rehearsing it with a friend or do a trial run. You could also speak through your worries and concerns by unfolding them with a friend. This could reduce some of the stress we predict might be involved with implementing the solution. Sometimes despite our best planning, there are factors outside our control that can influence the outcome. This is why we have a plan (solution) B and C available.

- Evaluate the outcome. We should be sure to reflect on how we went with implementing our options. What worked? What could have gone better? What would you do different next time? How has our problem-solving style changed as a result of this outcome? Learnings form your problem-solving application improve your skills for the future.

Problems are often part and parcel of life and can make accomplishments feel rewarding when we achieve them. But, when we experience them, they can feel scary, uncomfortable, permanent, and unsolvable. It is important that we identify what kind of problem solver we are and take steps to better our problem-solving skills not just for the present concerns but for inevitable future problems. This way, we can navigate life knowing that we are ready for what is to come.

References

Problem-solving therapy (PST) practice guide (no date) Problem-solving therapy (PST) practice guide | APS. Available at: https://psychology.org.au/for-members/resource-finder/resources/assessment-and-intervention/therapy-guides/problem-solving-therapy-pst-guide (Accessed: 15 January 2024).

Stuart, S. and Robertson, M.D. (2012) ‘Section 3, Chapter 13 Problem Solving’, in Interpersonal psychotherapy: A clinician’s guide. London: Hodder Arnold.